A few days ago I released the first version of the Streamplify library, which offers a series of useful streams (most of them related to combinatorics) and other utilities for building streams that allow efficient parallel processing.

I will not give an overview of the Streamplify library, because I already published an article on DZone about it. Instead, I will discuss the ability to shuffle the streams created with this library.

Shuffling a sequence is not a trivial task if the number of elements in the sequence is very large. Still, such large cardinalities occur frequently when working with combinatorics streams. Take for example the stream of all possible arrangements of the playing cards in a standard 52-card deck. There are 52! arrangements, which is a 68-digit number roughly equal to the number of atoms in our galaxy. Such huge numbers make impossible to store the elements of a stream. They have to be generated the moment they are needed.

The elements of a stream provided by Streamplify can be generated based on the value of the previous element in the stream or based on their rank.

The rank of an element is given by its index in the stream.

Therefore, shuffling the elements of a Streamplify stream implies defining a (pseudo-)random permutation of their indices.

For a stream with N elements, this means to generate a permutation of the numbers 0, 1, ..., N-1.

The problem is that N is often astronomically high.

An overview of the most common approaches for solving this problem is given in this blog post.

Some of the methods described in the blog can only generate the permutation elements in a sequential way.

This means, the K element of the permutation can be obtained only after generating the elements

0, 1, ..., K-1.

Such methods are not appropriate for Streamplify, because the stream source is sometimes splitted in order to parallelize operations, and the value of the previous element in the stream is not available immediately after a split.

The other methods are based on format-preserving encryption.

Some of them are restricted to predefined block sizes, while others require encryption keys whose generation is computationally expensive.

I took a pragmatic approach and devised a shuffling algorithm that is fast, memory efficient and decently scatters the elements, although not in a uniformly distributed manner. For a given index, each byte in its representation is handled separately. First, it is XORed with its successor byte (if it exists). Then, a permutation is applied on the resulting byte. The permutations to be applied to each byte are pseudo-randomly generated during the initialization of the shuffler. Each byte-permutation has only 256 elements, therefore they are generated fast. The algorithm uses only 4 byte-permutations, applying them in circular order. Because the BigInteger representation of a number may have a number of bits such that the most significant ones do not fit exactly in a byte, the algorithm also generates so-called bit-permutations to be applied on byte fragments. During its initialization, the shuffler creates 7 bit-permutations, corresponding to byte fragments with 1, 2, …, 7 bits.

Let’s consider that the algorithm has generated the following permutations:

bytePerm[0]: [3C, B3, 2B, BD, 64, FF, A9, 3B, 2A, EC, 81, 57, 35, 0A, D7, E3, ...] (256 elements)

bytePerm[1]: [99, 41, F6, 8C, E9, C3, 6E, 3C, E0, 22, 89, 15, 42, BC, 4D, A3, ...] (256 elements)

bytePerm[2]: [C5, 14, 42, 8C, 6A, 9F, 85, 86, 7C, 0B, 7A, C7, 93, 3D, BA, 40, ...] (256 elements)

bytePerm[3]: [D9, 74, 6C, 92, E8, DE, 07, C6, DA, 56, A0, F3, BA, A3, CC, 87, ...] (256 elements)

bitPerm[1]: [01, 00]

bitPerm[2]: [03, 00, 01, 02]

bitPerm[3]: [02, 05, 06, 03, 04, 00, 07, 01]

bitPerm[4]: [0D, 08, 0E, 00, 05, 0A, 09, 0B, 07, 03, 01, 0F, 06, 0C, 04, 02]

bitPerm[5]: [1D, 04, 18, 13, 11, 02, 10, 0A, 1A, 03, 00, 0F, 17, 05, 06, 12, ...] (32 elements)

bitPerm[6]: [06, 29, 20, 26, 01, 15, 3E, 19, 36, 07, 3F, 2E, 12, 0A, 1B, 28, ...] (64 elements)

bitPerm[7]: [15, 65, 5F, 43, 19, 60, 61, 57, 51, 56, 22, 24, 23, 6F, 6E, 21, ...] (128 elements)

We will apply now the shuffling algorithm to the index 2345678765432 of a sequence with 7654321234567 elements.

count: 7654321234567 = [06 F6 29 19 22 87] (43 bits = 5 bytes + 3 bits )

index: 2345678765432 = [02 22 25 59 7D 78]

idx <-- byte[5] = 78 ^ 00 = 78; shuffled[0] <-- bytePerm[0][78] = FB

idx <-- byte[4] ^ idx = 7D ^ 78 = 05; shuffled[1] <-- bytePerm[1][05] = C3

idx <-- byte[3] ^ idx = 59 ^ 05 = 5C; shuffled[2] <-- bytePerm[2][5C] = 71

idx <-- byte[2] ^ idx = 25 ^ 5C = 79; shuffled[3] <-- bytePerm[3][79] = F7

idx <-- byte[1] ^ idx = 22 ^ 79 = 5B; shuffled[4] <-- bytePerm[0][5B] = 86

idx <-- byte[0] ^ idx = 02 ^ 5B = 01; shuffled[5] <-- bitPerm[3][01] << 5 = 05 << 5 = A0

On each line in the listing above you can see the two operations performed on a byte:

executing a XOR with its successor byte and applying a permutation.

In the last line a 3-bit permutation is applied, because the representation of count requires 43 bits, thus containing a 3-bit fragment. Note that the obtained value is then shifted (8-3) = 5 positions to the left in order to join this 3-bit fragment to the other bytes.

Note also that the shuffled bytes are computed in reversed order. For example, shuffled[0] is computed based on the value of byte[5].

This way, any two consecutive indices will have corresponding shuffled values that differ in their most significant byte.

This leads to a good scattering of the shuffled values.

The drawback is that whenever the distance between two indices is a multiple of 256 (which implies that their least significant bytes have identical values), the most significant bytes of the shuffled values of these indices will be identical. In order to fix this problem, the algorithm performs a XORing of neighboring bytes in the shuffled value, starting with the next-to-last right byte:

from right to left XOR with next byte: FB C3 71 F7 86 A0 --> 98 63 A0 D1 26 A0

Finally, the resulted shuffled value is shifted (8-3) = 5 positions to the right in order to obtain a number with the right magnitude:

shuffledIndex <-- BigInteger([98 63 A0 D1 26 A0]) >> 5 = 167553667245728 >> 5 = 5236052101429

The BigInteger representation of the shuffled value has at most the same number of bits as the representation of the maximum allowed index (that is, count-1).

Still, it is possible that the shuffled value is greater than the maximum allowed index.

In this case, the algorithm will be run again with the shuffled value as the input index.

This process is repeated until a shuffled value in the admitted range is obtained.

As mentioned before, the values generated by this algorithm are not uniformly distributed. This can be demonstrated for example by applying the Chi-squared test. However, the shuffled values are nicely scattered, which means that the algorithm is good enough for most practical purposes.

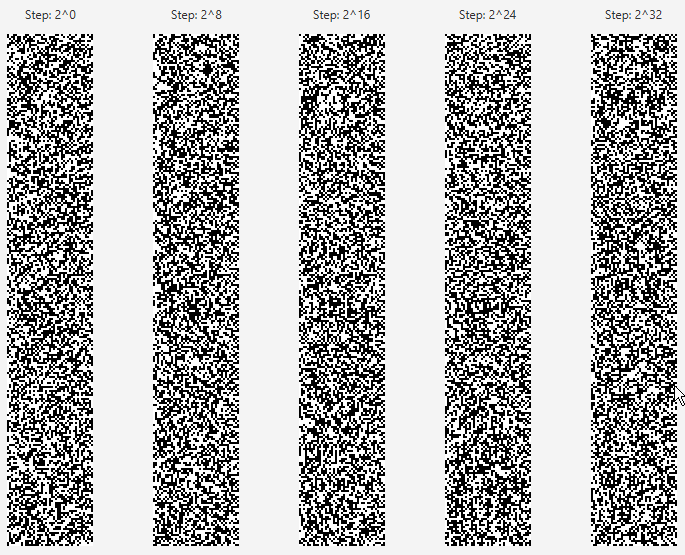

I wanted to see if it’s possible to observe that the shuffled values are not exactly random without using statistics tests. Therefore I wrote a small program that displays shuffled values based on their binary representations. Each value is shown as a line with black pixels for 1s and white pixels for 0s. One drawback of the algorithm is that the permutations are applied on each byte separately, which makes that two indices with one identical byte in the same position will also have one identical byte used in the construction of their corresponding shuffled values. Thus, it is more probable to observe non-random patterns for indices at distances that are multiples of 256. The figure below has five columns, each corresponding to a sequence of 256 indices. In the first column, the indices have consecutive values. In the second, they are an arithmetic progression with the common difference 28 = 256. In the third column, they are an arithmetic progression with the common difference 216, and so on.

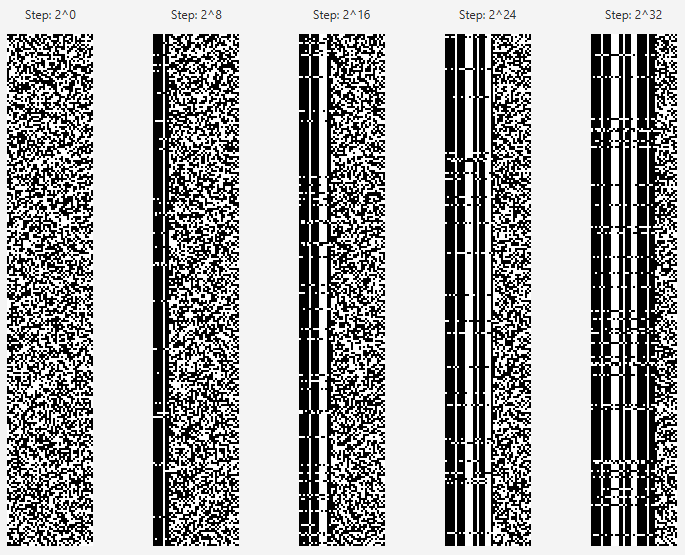

Everything looks pretty random in the above image, which means that the algorithm does a good job at hiding its flaws. But a simple modification will change this. Starting from left, let’s XOR each byte with its successor. The result is shown below:

Except for the first column, where indices have consecutive values, the other ones exhibit non-random patterns. The number of stripes grows with the exponent used for the common difference in the arithmetic progressions.

Should you worry about this? No, unless you intend to use the shuffling algorithm for hardcore scientific research. In practice, it is very unlikely that you will observe any non-random behavior, so use the shuffler along with all the other goodies provided by Streamplify.